What was the very first Brian DePalma movie you remember seeing?

Peet: That's difficult. I was probably a little too young for it, but it may have been "Sisters.” Yeah, but I think the first thing I remember from Brian DePalma was that he was on television, because "Body Double" had just come out, and I saw the clips from "Body Double" and I thought, wow, that would be something I would like to see. But I was too young for it.

I wasn't able to go into the cinema and check it out, but immediately I made a mental note. And I think the name just stuck with me. And I started to check him out, and whenever there was something on television, by him, the BBC or whatever, I would definitely see it. So, it might have been "Sisters.” It might have been "Blowout," I'm not really sure.

My point of entry was "Phantom of the Paradise." It was first released in cinema, and I'd never seen anything like it, and then had to follow up with this guy, Brian DePalma, to see what he was going to do. And the next thing I remember seeing was "Carrie," and really loving it.

I remember it was showing maybe a couple years later at a University Film Society, and I wasn't seeing it, but I was walking by. I could hear what was going on, and I said to friend, “let's stand here for just a second, they're about to scream,” because the hand was about to come up out of the grave. And it was so much fun to just know that was going to happen. And then years later to read about how Paul Hirsch came up with that and the music choice that he made and all that. So, is there a favorite Brian DePalma film?

Peet: Yeah, I think "Blowout" is my favorite. It seems to be the one that combines all of his best qualities, you know, combining hot and cold and his formal expertise and his weird plotting and humor. Yeah, all of that.

He does have both weird plotting and very devious humor and all of those, I wouldn't say it's my favorite, but I do whenever it's on, I can't help it, watch "The Fury." Just because it's a filmmaker working so hard to make this work. The cast is great, and they're all giving it their all and you know, the story doesn't really hold up. But he is just throwing so much at it to make it work that I appreciate that.

Peet: That's a good summation, actually. Yeah, it doesn't really work, but it's just so much fun.

Yes, exactly. One that I have trouble finding that I just love and that I just looked it up (as I mentioned, I was just looking to see the order of things), and I'm surprised that “Obsession” came before “Carrie.” I thought it came after “Carrie.” And that's his first time working with John Lithgow, and it's from a Paul Schrader script. And apparently, the last third of the movie they didn't even shoot. There's another whole act of it.

Peet: Yeah, I think Paul Schrader is still a little pissed off about that. Even, more than a little.

Maybe more than a little. Well, and with every right. But I think what Brian DePalma ended up doing with that movie—particularly when you read in Lithgow's book about the difficulty he had working with Cliff Robertson, and how difficult Robertson was and how he sabotaged every scene he was in to make sure that he would get the close ups, which is such a weird thing to want to do. But I guess that's what he did. It's with that Herrmann score. It's just such a lovely movie that I wish I could find it more often, but it is hard to come across.

So, what did you think of "Raising Cain," the first time you saw it?

Peet: Well, I know it like today, it was yesterday, because I discovered him while he was in the middle of his career. And so a lot of the films that I saw were actually older films of his. And I really liked his thrillers and the films that really carried his own signature. And at the time, he had been doing some other kinds of pictures. I think "Wise Guys," was one of them, I didn't even bother to see that. And, of course, "Bonfire of the Vanities," which was not exactly praised.

It wasn't, but it's not horrible. It really isn't horrible. I rewatched it recently, and it's got some wonderful stuff in it.

Peet: Yeah, they always do. All of his films have wonderful stuff. But anyway, it was pretty clear from the promotional materials and interviews that he was doing something with “Raising Cain,” which sort of pointed towards the fact that he was starting to go back to the source, you know, he was going to do his own thing again. And I was completely ready for it. And I had a girlfriend at the time and I must have, you know, been enthusing a lot about it. And she went with me, when it was out in the cinemas. And I liked the movie very much because I was a die-hard, rabid fan. But my girlfriend, she was sitting next to me, and I could feel she wasn't liking it. And after, I think already about four minutes in, she turned to me and said, “what kind of crazy film is this?” And, you know, this was also in the cinema that we saw it, you know, this was the general consensus. It was like, what kind of crazy thing is this?

Now, would that have been the car scene with Carter, and the woman and Cain shows up in the window?

Peet: It's going off the rails really soon in the original version. I was ready for that because I was a Brian DePalma fan. So, I dug it. But I also could completely understand why the casual viewer would have lots of problems with it. So, that stuck with me. Of course, later I found out that Brian DePalma wasn't really happy with how the film turned out. And when I sort of guessed what he originally had in mind, I thought that would work much better, actually.

Yes, it's much more keeping with “Dressed to Kill” and “Psycho,” where you start the story one way andwe don't learn who the villain is until much later. With that in mind, and with enjoying the film, what was it that inspired the re-cut?

Peet: Well, I was hosting a website with a forum on it, that had a lot of the Brian DePalma fans, who actually made the jump from another forum that was specifically about Brian DePalma. So, there were a lot of Brian DePalma fans there, and they were discussing lots of stuff. And at a certain moment, there was this guy who was talking about an interview book he was doing with Brian De Palma. He must have mentioned “Raising Cain” and that DePalma had said in the interview that he wasn't happy with it. And that immediately piqued my interest.

And I asked Laurent, what was it about the film that he doesn't like? And Laurent said, well, he originally wanted to start with the story of the woman. So, that was the point where I thought, yeah, of course, then that probably means that he would start in the clock store, I immediately thought. So I checked out my DVD, and I tried—you know, the DVDs have chapters—so I tried to reorder the chapters to see how that movie must have played originally. And I couldn't really get it to work. But I still thought there might be a better film in this than was originally released.

So, with that in mind, how'd you make that happen?

Peet: Well, I left it alone for a few years. And at a certain moment, I guess it bugged me. The idea kept sticking in my mind, and I thought, well, why don't I just try it> And I ripped the DVD, and I am a director and editor, so I know how to edit. And I started asking around and Jeff who has a DePalma website knows a lot of stuff about the Brian DePalma. He actually had an old draft of the screenplay. It was called Father's Day at that time, and he was willing to send it over to me. So, I was able to read that. And indeed, the movie started the way I mentioned it, in the shop. But there were a lot of things different back then, because the screenplay wasn't completed. There were some really wild things in there that he just let go because it was too wild, or he went into another direction. But basically it laid out how the chronological order used to be.

It wasn't actually chronological. He made it chronological because, as I heard it, he started to second guess his own creative feelings when the movie was tested and people had a problem with it. He started to mess around some more in the editing, and he changed everything to a chronological order. At the time, he thought, well, this is probably better, because then we get to the action really soon. Yeah, we do. So, that is how it was released, but of course in interviews after that, he has mentioned a lot about the fact that he doesn't really like the film as it was released, and that it should have been different.

Before chatting with you, I sat down and rewatched both versions and took notes to try to figure out what the order was. And what throws it off for me a little bit is the opening shot in the theatrical cut of the park from high up is very much a Brian DePalma opening shot, you know, very close to what he did in “Carrie.” Whereas, the opening shot in the clock store is not really a DePalma shot. It's a little mundane. It's a wide shot. It's interesting, you know that Jenny walks up and sees herself in the heart shaped camera and all that--

Peet: It encapsulates the whole movie, but that's in a different way than the original did.

Yes, exactly. And then as I was going through—and I'm sure you ran into this, it's regardless of whether it's the re-cut or the theatrical one—it's a dream sequence with a flashback built into it. And so it isn't until you get out of the dream sequence that you realize, oh, that was a dream sequence. But then in your mind, you're going well, then, was the flashback real, or is that part of the dream?

And then they've added in narration as part of the flashback to help explain it, which I'm guessing was done in post. And so now they have a narration thing. So they have to keep that up. And then when they switch it around, when you did the version that was closer to what he wanted, it's still a bit wonky, regardless of whether you're chronological or not. And the audience has to go: okay, she's going to the hotel. Is this a dream? It must be a dream, because she's walking into the room and she doesn't have a key. That's the only clue, I think, that it's really a dream. And then obviously it's a dream, because she's killed and wakes up. And then you have the repeat of the thing with the gift and all that.

So, regardless of the order of everything before, that whole section, I think is always going to throw an audience off.

Peet: You're right, but the wonkiness, if you call it that, it is intentional. What he wanted to do, and he has stated this in interviews is, you know, normally with kind of police mystery, there is something going on and you don't know quite what. And then the detectives, they start to ask around. And you slowly assemble information, and it becomes clearer and clearer what actually has happened. And he really wanted this time to fuck with his audience, of course, because that's what Brian DePalma does. And he said, what if all the information the audience is getting is either a dream, it has never happened? Or they don't know if it's happened. Or, you know, it's an unreliable narrator. That was actually the game.

And he's so good at that.

Peet: He's really good at it, but of course you also need to get the audience so far that they're willing to go with you. Because it's a very manipulative way of telling a story. And some people don't like that. So, that's a very thin line that he was walking.

And I think in the editing, he got cold feet. He thought, well, maybe I went a little too far here, and maybe I should do it a little differently, help them out and make everything chronological, and it may have fixed some things. But it created other big problems. The flow isn't really right. It wasn't how he originally imagined it.

I think in a way he tested it, and it tested badly. And after that, they changed it around, and I think probably some of those changes were good, because he also shortened some bits, which were maybe a little too wild, judging from the screenplay that I've read. But I think changing the order was a bad decision. And I think he thinks that too, because as you know, he actually likes the version that I did and it's the "Director's Cut."

So, he fixed some things, and he made other things problematic. It's really funny, you mentioned Paul Hirsch earlier, and he's, of course, De Palma, editor. He originally wasn't the editor on “Raising Cain,: it was someone else or two other people, and it didn't really work out as the Brian DePalma wanted it. It says in the book. He was struggling with it in the editing suite, and at a certain moment, I guess, he fired the previous editor. And he made sure that Paul came in. And Paul, he read the screenplay on the airplane, and he didn't get it.

That's a bad sign.

Peet: And he read it again, still on the same flight still didn't get it. He went to the Brian DePalma, he asked about it and still did not get it. And while he was editing, I'm afraid to say he never really got it. And that was an eye opener for me. I realized that pretty late on, because that book came out sometime after thae "Director's Cut" had come out on "Blu Ray."

He was also asked, he was giving a Q&A somewhere, and somebody mentioned the Director's Cut, that it was edited by some random guy, and DePalma actually preferred that version. And Paul Hirsch said, well, he should have hired the random guy. Well, in a roundabout way I did it. But don't get me wrong, though. Paul is brilliant. He must have done a lot of things right as well, because I think the finale of the film, which all plays in slow mo, I think he edited that all over again. And that works brilliantly.

It does. If you remember what he did at the end of “Carrie,” and how he fixed the split screen issues in the end of “Carrie” and made all that work. The montage he put together in the middle of "Phantom of the Paradise," even the closing credit montage in “Phantom the Paradise” in which you really recap all the characters. That's a really good editor.

I understand that for legal reasons—in putting together your recut and making it what became the official Director's cut—you had to use all the elements from the theatrical cut. You had to use all of them, and obviously couldn't add anything, because you didn't have access to that. Was that tricky, where you had to use absolutely everything?

Peet: No, it wasn't tricky. I was just lucky. When I made my own recut, and De Palma wanted it to be part of the Blu ray, the lawyers of Universal also requested that the recut of the film would only be possible if it wouldn't add something and wouldn't take something away. And, yeah, I was just lucky that it works like that. The only thing I did was change the order around, and there's a little change in the overall length of the film. That's because I repeat something, and I make some dissolves little a differently.

That repetition is really helpful, to pull us back to where we need to be on the timeline. If you didn't have the scene that Jenny and her friend played by Mel Harris, I think you would get a little disassociated as to, okay, it’s the same time, they're in the park.

Peet: Yeah, I think you're absolutely right. And this must have been one of those things where an editor can help a director to achieve what he wants. Because I can imagine that they tried out that order in the editing suite. And that they thought it wouldn't work, because it's too jarring, you don't know where you are in the story, whatever. And the little repetition that I added really helps to get the viewer—you know, it is still jarring—but immediately after that the audience realizes, “okay, it's this moment, right,” and then they get along with it again.

I’m wondering if today's audiences today might be a little more keyed into time jumps than they were back then?

Peet: Definitely, because since then, of course, we've had movies like "Memento" and "Pulp Fiction," which are, you know, messing around with traditional ways that stories are told.

I think part of the problem was that you have this huge flashback, and at a certain moment, the movie goes on again, after that flashback. But it's such a long flashback that Brian DePalma thought, well, maybe the audience will never understand that a flashback can last that long. So, let's not do it. And I think, you know, the movies that I'm mentioning, other ones might have helped to educate the viewer to the modern age where this is not much of a problem anymore. You know, you can, take people to amazingly difficult things. You just watch what Christopher Nolan has been doing, and they are willing to go along as long as you entertain them and reward them.

In comparing the two versions as closely as I did, your version, although it's just a tiny bit longer, it actually seems faster. Because once Carter gets on that Carter train where he has to go all the way to the end, that's happening more in the middle of the movie, instead of the beginning. That just gives it a propulsion that the theatrical version doesn't have because it starts with Carter, and then it goes to Jenny for a big chunk, and then it's back to Carter. You're getting a little surprise of, oh, John Lithgow is evil in the first five minutes. But it's John Lithgow, so how big a surprise is that going to be in a DePalma film, really? I don't think he's ever been in a DePalma film where he wasn't ultimately evil.

Well, it's true. And then switching it so that we're doing the Psycho/Dressed to Kill thing, following a character and then she suddenly dies. But then DePalma’s brilliant touch of, no she is not dead, when Carter sees her on the TV screen is a huge shock. And I think it’s more of a shock in your version than in the original one, and just because of the pacing of things.

There is still though in both versions my favorite moment, and it's one of those things where I wish I could go back and see it again for the first time: when the elevator door opens and you see "Dr. Nix" coming forward with the baby. And you realize he is alive, that he isn't a manifestation of Carter's brain. He's really there, and we've been toyed with all the way up to that point with obviously, “he's not there because he's never in the same shot with anybody else.” He's doing the same tricks that he does with Cain. It's just such a delightfully DePalma moment, that and the appearance of Jenny on the TV screen, are just great moments that only work because the filmmaker has brought us up to them so skillfully.

Peet: Yeah, you're right. You know, that is the original flow as it was intended. It's also funny to me that a lot of people at the time didn't really care for the story of Jenny, because you know, you were already on this track of John Lithgow doing his crazy thing, and then you all of a sudden get a love story. I loved it at the time, but it didn't play that well. So, it's kind of brilliant that if you start with it, it really gets the attention that it deserves, and people actually really like it, and then as soon as John Lithgow does his thing, like you say, it becomes really propulsive, the whole narrative goes toward that ending.

Yeah, it's just great, and of course, we can’t not that mentioned DePalma's lovely play on "Psycho’s," ending scene with Simon Oakland explaining everything. To have France Sternhagen do that same thing in her own way. And then, of course, that classic DePalma shot taking us all the way through the building for no other reason than the fact that he can, in fact, do that. And just watching it, thinking, wow, she's timed exactly where she goes off kilter, and they have to pull her back, and it all fits with the lines as she's saying them.

When he does that sort of thing, like he did at the beginning of "Bonfire," it's just so much fun to watch him do it because you realize not a lot of filmmakers can pull that off and keep the right pacing and make it work. It's just a great moment. He's such a devious, master storyteller.

And then let's just jump ahead: You make the cut, and you heard that he loved it. How did that happen?

Peet: Well, I think a year after I put it online on IndieWire. I talked about what I was doing, and I thought, wouldn't it be great if I make a video essay about my findings, and then it was posted on IndieWire. And he said, I think the whole version should be on IndieWire. And that, of course, you know, in terms of rights, we were thinking like, can we do that? Actually, you can't really, but we decided to do so anyway, and then put up that it was for educational purposes. And we just decided that whenever Universal lawyers would call, like, what are you doing, get this thing off? We would get it off. But it was on there, and I believe it's still visible actually.

They don't really care for Raising Cain at Universal, but Brian DePalma, he found it. And about a year later I started reading in interviews—I think there were at least five—that he actually preferred this version over his own version. And that was of course already completely wonderful.

Much later, I think about five years later, the Blu Ray was announced by Shout Factory. And all of a sudden Jeff from the Brian DePalma site—I mentioned him before—he got an email from DePalma. He said, “I just watched the Raising Cain recut and I think it's great. It succeeds in things that we couldn't get right the first time. It is what I originally wanted the movie to be.” And he thought it should be part of the Blu ray and he said, “Maybe you can make this happen? If I have to call somebody, then I will.”

So, that is how it happened. It was a big surprise for Shout Factory. I think they already finished the Blu ray, and then all of a sudden they got this call from the director, like okay, yeah, well, you have to add something.

There's now going to be a second disc.

Peet: Yes. I never talked to Brian DePalma, but he basically gave me free rein. He said, “Okay, I've liked this version, this recut and it should be on the blu ray.” So, Shout Factory asked me to make that happen. We used the original master, the same master as was on the normal blu ray, and we actually re-edited that according to the recut that I have made and put it on the blu ray.

That's an incredible story. What a thrill for you and what a vindication for him that somebody somewhere did this because of today's technology. It'd be like if you got a letter from Orson Welles, saying thank you so much for restoring "Magnificent Ambersons," that's exactly the movie I set out to make.

Peet: It’s still a little bit of a dream when I think about it. It's really great and I know I've emailed him after that to try to get, you know, some of the correspondence about it, but he's not the kind of guy who answers those emails. But I do know actually from Laurent who did the interview book that DePalma’s very happy with the blu ray as it is right now.

You feel, sort of, it has validated his film again. So, that feels great.

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

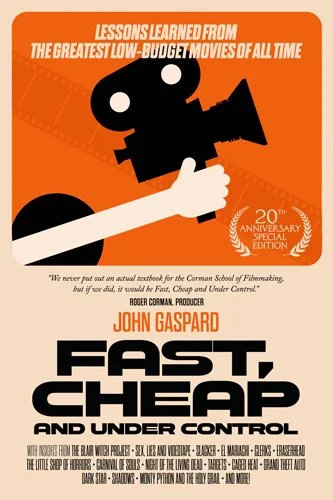

When Fast, Cheap & Under Control first hit shelves in 2006, it became the underground handbook for a generation of indie filmmakers. Now, two decades on, this 20th Anniversary Special Edition proves the lessons inside aren't just timeless—they're more essential than ever.

What's changed? Technology. Platforms. Distribution.

What hasn't? The grit, ingenuity, and sheer determination it takes to make a great film with nothing but vision and hustle.

Inside, you'll find:

Exclusive interviews with legends like Steven Soderbergh, Roger Corman, Jon Favreau, Henry Jaglom, Kasi Lemons, Dan O'Bannon, Bob Odenkirk and more

Over 100 images bringing the stories to life

40+ links to trailers, scenes, and supplementary material—turning this book into an interactive master class

Real-world case studies from 33 groundbreaking low-budget films—from Clerks and El Mariachi to The Blair Witch Project and sex, lies, and videotape

Field-tested lessons from the author's own four features—proof that these principles work in the real world, on set, in the edit room, and on screen

Whether you're shooting on your phone or scraping together a micro-budget, this is your master class in turning limitations into strengths.

No film school required. Just this book.

Roger Corman called it the textbook for his legendary filmmaking school. Now it's your turn to learn from the best.

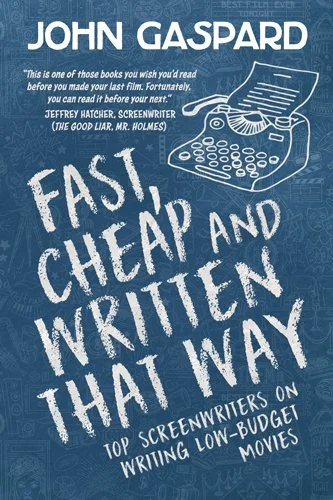

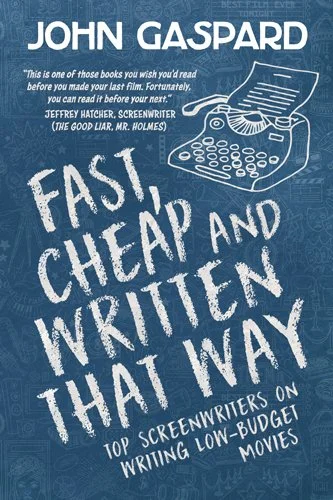

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!