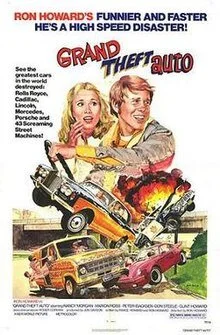

Like many of the other top directors of his generation, Ron Howard’s directorial debut came via Roger Corman. Not only did Howard direct Grand Theft Auto, but he also starred in the film and co-wrote the script with his father, actor Rance Howard.

RANCE HOWARD: Ron had acted in (Corman’s) Eat My Dust, and it had been a huge success for Roger. He wanted to do another car chase/car crash film. Ron said, “I will do another movie for you, with one additional job added.” And Roger said, “What is that?” And Ron said, “I want to direct.” And Roger said, “Well, Ron, you always looked like a director to me.”

How did you and Ron come up with the idea?

RANCE HOWARD: Roger already had the title. He had tested it. It was going to be called Grand Theft Auto, and it was about young people on the run. He said, “If you and your dad could come up with a story like that, we'd have a deal.” So, we sat down and put our heads together and started kicking ideas around. We did a treatment first; Roger read the treatment and loved it and we went right to script.

NANCY MORGAN: I was told that Roger had a certain formula that was applied to this type of picture. There were a certain number of explosions that had to happen, there a certain number of recognizable names that had to be worked in. There were elements that were almost like Julia Child's recipe for making money. The bases were covered methodically.

RANCE HOWARD: I was fascinated with the demolition derby. At one time, Ron, Clint and I went to see a demolition derby, and it was just fascinating. At that time, I had considered writing a script about a demolition derby. Then with Grand Theft Auto, it just seemed perfect for the car to end up in a demolition derby.

NANCY MORGAN: Ron told me, during the shoot, that Roger had told him when he made this deal, "If you do a good job for me, you'll never have to work for me again."

One thing I’ve heard from many directors who’ve worked with you on their first films is that, before getting started, you take them out for what is called The Lunch. This is where you distill all the best advice about how to successfully execute a low-budget Corman film. What are the elements of that conversation?

ROGER CORMAN: It's too involved to get into here. But the most important thing that I point out over and over is preparation. On a ten-day shoot, or a 20-day shoot, you don't have time to create from scratch on the set. As a matter of fact, I don't think you should do that anyway. My number one rule is to work with your actors in advance, so you and the actors are agreed on at least the broad outline of the performance. Then to have sketched out, if not all of your shots, most of your shots, so you have a shot plan in advance.

How did you first hear about Grand Theft Auto?

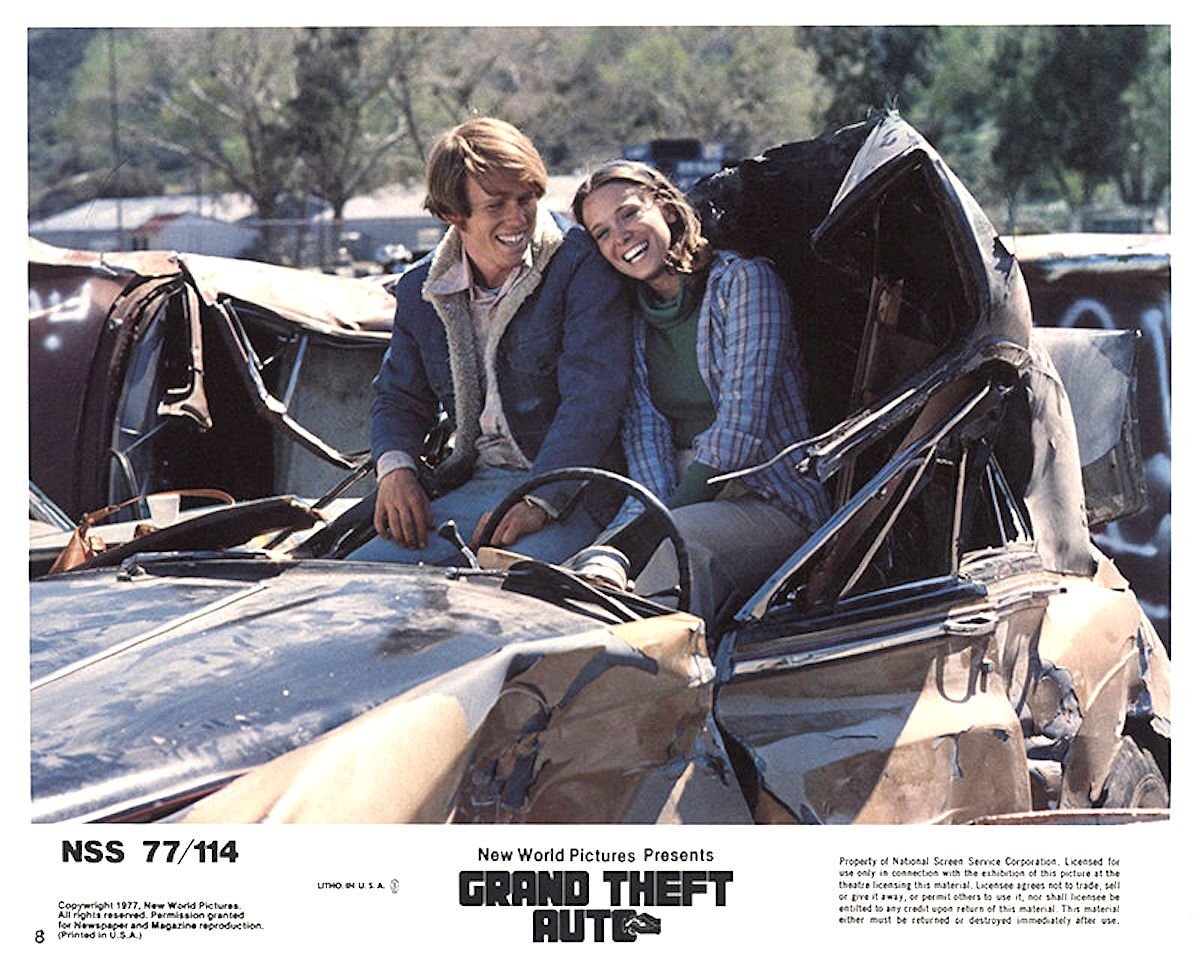

NANCY MORGAN: My agents were contacted by Ron! Can you imagine? When he was casting for this role, he was looking for someone who, first and foremost, he didn't have to pay a lot. It couldn't be a star—it had to be an unknown. At the time, one of my first movie that I'd ever acted in—in fact, one of my first acting jobs ever, because I came to Hollywood untrained and unprepared—was a movie called Fraternity Row, with Paul Newman's son, Scott Newman, in his first and only picture. And it was out in the theaters when Ron was casting, and he liked my performance in it and found my agent.

What was the audition process like?

NANCY MORGAN: Back then I used to say to myself, “There are a lot of people here who know a lot about acting, but all I really know is that you just have to pretend that it's happening.” And so, during the audition process, I did as close to what I felt a human being would do under the circumstances, and that was to say the lines like I meant them, and then when Ron was talking to me, react to what he was saying. And that was about as much acting as I knew. Ron later said to me, “You know, I interviewed a couple hundred girls. Did you ever wonder why you got it? Because you were the only one who, when you weren't speaking, was still listening.” That was something that forever stuck with me as one of the things that was important and not everyone's top tool.

Once you had the script and cast in place, what was the next step?

RANCE HOWARD: I always knew that preparation and rehearsal are extremely important. But this experience drove that fact home and really solidified that. Preparation is really, really important. Pre-production, really being prepared.

ROGER CORMAN: I'm a strong believer in rehearsals and in pre-production and preparation. I want to be able to come onto the set and shoot. Ideally, everything is worked out in advance; practically, it never quite works that way. You always are faced with new problems, or maybe you get a better idea. But at least you have your framework before you shoot. If you don't have time for a full rehearsal, I like to have at least a reading with the actors, in which we read and maybe do some improvisations and do some loose rehearsals—not on the set—taking at least one day before shooting for that.

NANCY MORGAN: The cars rehearsed. The stunts rehearsed. And the explosions rehearsed. We basically just had to know our lines and pretty much bring it to life. We would run through the scene once or twice, but really rarely for the acting of it. Ron knew what he was doing, so he didn't really need it.

ROGER CORMAN: What I do, and what I tell my directors working with me, is that you waste a lot of time after you get a shot, where you're congratulating everybody, discussing the shot, and so forth. And that shot is already yesterday's news. You've got it. So, what I do is I say, “Cut, print, thank you.” Then maybe one sentence saying how good it was to the actors. And then, “The next shot is over here.” And we're on to the next shot.

With Ron’s focus on directing the movie, what was it like to act with him?

NANCY MORGAN: Looking at the script, there appeared to be a thousand interchangeable scenes of Ron and me in the car, talking about this and that. I understood enough about story to know that it had to build and climax and resolve. And so the first thing I did with my script was to break it down into an outline and had an understanding of where Ron and I were in our relationship, from the first scene to the last. Ron, on several occasions—since he was in charge of the whole picture, directing everything—he realized that I had done this and that I was aware of where we were in the script at any given point in terms of his and my relationship. He would sometimes say, “Where are we?” And I would say, “Well, this has happened, and this has happened, and this has happened, but this hasn't happened yet, so we do know about this, but we don't know about that.” And he'd say, “Okay. Got it thanks.” My breaking it down was something that I could do that was helpful to him and that would orient him as to where we were in the scene, and then Ron just acts—he doesn't even to have to worry.

The production really was a family affair, wasn’t it?

RANCE HOWARD: I think any director likes to use people that he is familiar with and that he can trust and has confidence in. Both Clint and I fit nicely into those categories. And his mother, at that time, had been working quite a lot coordinating extras for other filmmakers. And so, she coordinated a lot of the extras for that film, in particular the senior citizens on the bus. Involving his mother, and his brother Clint—an excellent actor, and who was at that time, almost as big a name as Ron—in the film just made good sense.

NANCY MORGAN: The other thing I learned on that movie is that there's nothing like family to pull this together. On this film, Cheryl did a lot of the cooking. His mom was in it. His brother was in it. And Rance, of course, co-wrote it with Ron. There was no partying for them. You never found them in the bar, sitting around, schmoozing with people. At night they were in their room, looking at dailies. They were looking over every single moment of this and discussing it like you would discuss an art project. They wanted it to be the best car picture it could be.

Was there any improvisation on the film?

NANCY MORGAN: The only improvisation was our kiss. Although it was written in the script, we didn't have a clue how to go about it. And that was the time where the whole, entire family got involved. Cheryl was standing by the side, with lip gloss and breath spray. And Rance was coming up and whispering in my ear, “Just go for! Go for it!” Which was his only direction to me in the entire film. So, it became my responsibility to just lunge for Ron and just, like, smack him. With everyone in the whole family standing around. That was probably the most improvised moment.

ROGER CORMAN: Be flexible. Even though you've done all your preparation, don't stick absolutely to the preparation if it doesn't seem to be working. Know that you've got the preparation, but situations change, so be prepared to change with the situations.

RANCE HOWARD: You need to be tenacious; you need to stick to your guns, but at the same time, you have to be prepared to compromise and negotiate. That was really driven home to me, the importance of compromise. There are a lot of aspects of making a film where you can compromise. In some places, you can't. You need to know what compromises can be made and what compromises can't be made. Coming to that realization is important: understanding that you're not going to get everything you want, you're going to get part of what you want.

What was the preview process like?

ROGER CORMAN: I'm a firm believer in putting the film, at least one time, before an audience.

RANCE HOWARD: We had the film assembled as a rough cut. Roger started going through and taking all the humor out of it; he didn't realize that Ron and I had designed a comedy. So, we rented a screening room over at Warner Brothers and invited some people to come and see it, along with Roger. The crowd saw the humor and they absolutely roared. When it was over, he came over to us and said, “You guys have a funny movie here.” After that screening, when we proved that we had a comedy, we had one or two more test screenings before we locked it up.

What was one of your biggest take-aways from the experience?

RANCE HOWARD: Stand up for what you believe in. For example, if we had allowed ourselves to be easily talked out of it being a comedy and cut it as a straight action picture. And filmmaking is a team effort, it's really teamwork. We happened to have a great team.

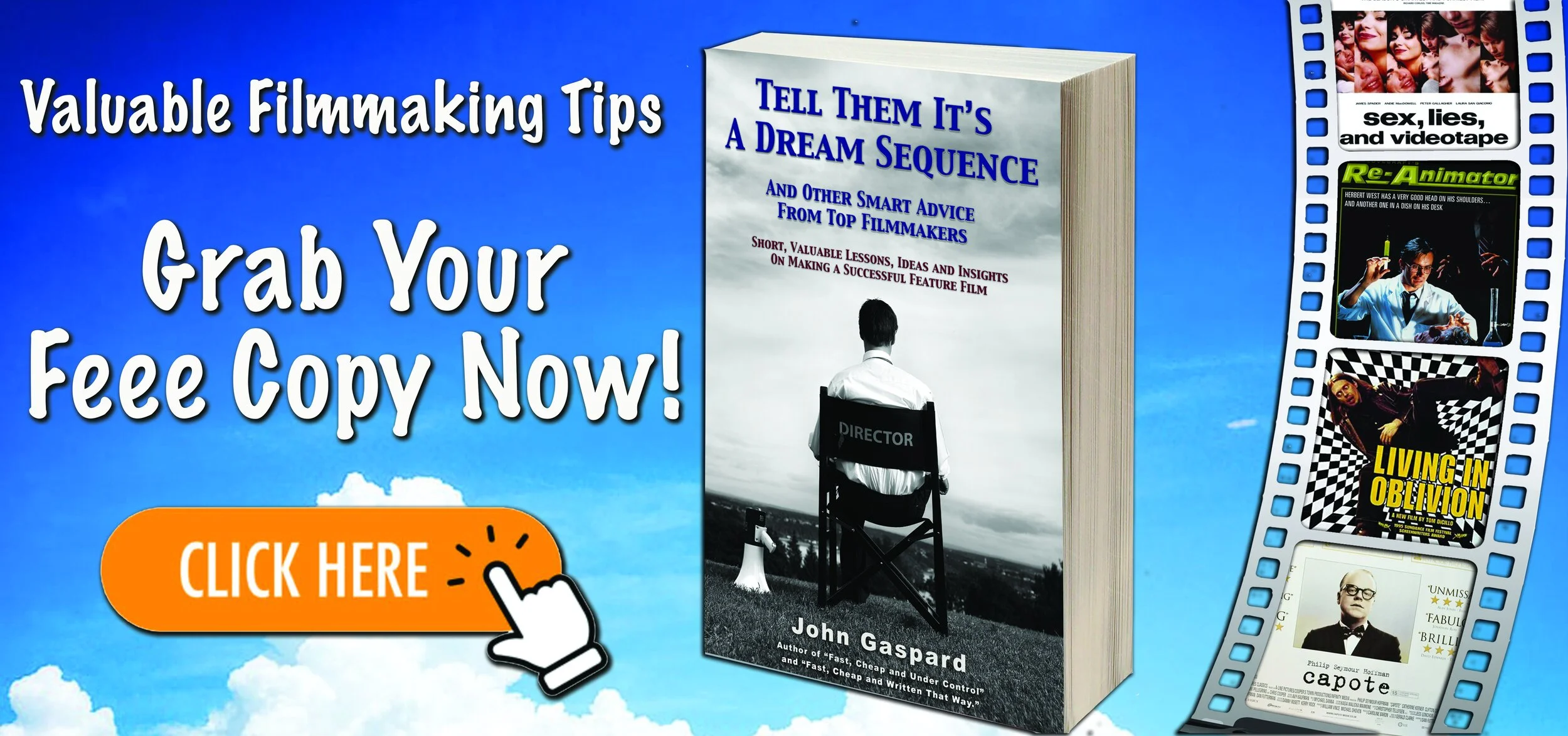

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

When Fast, Cheap & Under Control first hit shelves in 2006, it became the underground handbook for a generation of indie filmmakers. Now, two decades on, this 20th Anniversary Special Edition proves the lessons inside aren't just timeless—they're more essential than ever.

What's changed? Technology. Platforms. Distribution.

What hasn't? The grit, ingenuity, and sheer determination it takes to make a great film with nothing but vision and hustle.

Inside, you'll find:

Exclusive interviews with legends like Steven Soderbergh, Roger Corman, Jon Favreau, Henry Jaglom, Kasi Lemons, Dan O'Bannon, Bob Odenkirk and more

Over 100 images bringing the stories to life

40+ links to trailers, scenes, and supplementary material—turning this book into an interactive master class

Real-world case studies from 33 groundbreaking low-budget films—from Clerks and El Mariachi to The Blair Witch Project and sex, lies, and videotape

Field-tested lessons from the author's own four features—proof that these principles work in the real world, on set, in the edit room, and on screen

Whether you're shooting on your phone or scraping together a micro-budget, this is your master class in turning limitations into strengths.

No film school required. Just this book.

Roger Corman called it the textbook for his legendary filmmaking school. Now it's your turn to learn from the best.

And more!

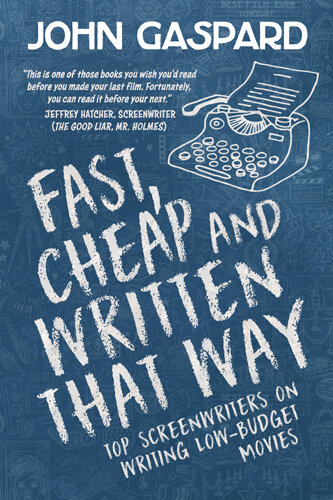

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!