How did you get your start in filmmaking?

WILLIAM: I taught acting for quite a while in Canada, from the Actors Studio in New York. I went up to Canada and worked on the National Film Board of Canada, on the production staff. I also, concurrently, opened up a studio that was modeled on the New York Actor's Studio, and taught acting.

One of my actors became very wealthy in the real estate business in Miami, Florida. He said, “Listen, you're a very talented fellow and you have a lot of ideas. You're just as good a director as anyone coming out of Hollywood. Why don't you do a feature?”

And I said, “These things cost money.” And he said, “What does it cost?” And I told him and he said, “Do it. I'll back it.”

So I asked him what sort of subject he wanted me to concentrate on -- a whodunit or a romance, or what?

And he said, “Anything you like. Whatever you want to do, Bill, you do.”

So, with that blank check I reflected on a lot of things that that I had been thinking about over the years. One of them is the creative process, as it relates to the actor and the director. Having been a product of the Actor's Studio and Lee Strasberg, Kazan, Stanislavsky and those people, as well as having been involved in psycho drama, by way of J.L. Moreno, who was the pioneer of psycho drama, it came to me that it would be interesting to shoot a film that had some of these elements.

I thought it would be interesting to do several screen tests and to look at the creative process that actors undergo, in conjunction with the director, to show their talents at the highest level.

So that was the beginning of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One?

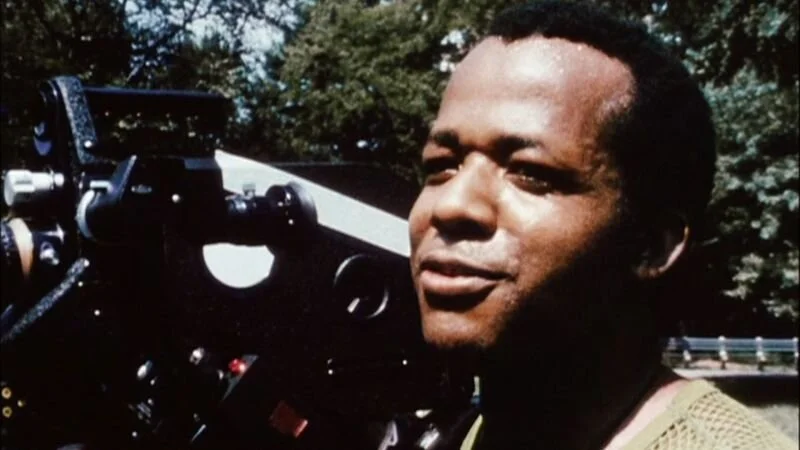

WILLIAM: That's how it all got started, initially, but then other elements came into play. For example, the Heisenberg Principal of Uncertainty, for which the analog to the electron microscope is the motion picture camera, which is looking down into the psyche and soul of the actor while the actor is performing, and often times it tends to stiffen and destroy the spontaneity and truthful feelings of the actor as the character they're trying to portray. I thought that would be an interesting element to think about, artistically, creatively.

One of the hallmarks of the Stanislavsky system is to try to be as honest in what you're doing, in performance, as possible. One of the things that kept bothering me about a lot of Hollywood movies was that the acting was very stiff and lacking in spontaneity. Having challenged myself as an actor to be more realistic in my acting -- and having looked at the work of people like Marlon Brando and Julie Harris -- people at the Actor's Studio whose work was very spontaneous.

It came to me that this was a wonderful opportunity to test the limits of my credibility as a person in front of a camera, pursuing this particular screen test with these actors, but trying to not act for the camera.

Talk about your character, the director of the screen tests.

WILLIAM: One of the elements of my characterization was my inscrutability. Try and try as much as they could, they couldn't decode my motives. That was calculated to elicit a degree of tension and anger and anxiety in the crew. They couldn't decode my motives, and I didn't want them to decode my motives, because I wanted to see if it would be possible to generate as much conflict in front of the camera as possible. Conflict being the hallmark of a really good drama.

I come from a wonderful high school here in New York, called Stuyvesant High School. That learning experience was very focused on science and the scientific method, and I've fallen in love with a lot of scientific principles, one of them was the Heisenberg Principal of Uncertainty. It seemed interesting to see how I could mix all of this.

I put all these ideas into a big pot and stirred these all of these diverse, disparate elements together and heated it up with conflict and served it up to the audience.

How much was the movie a product of its time?

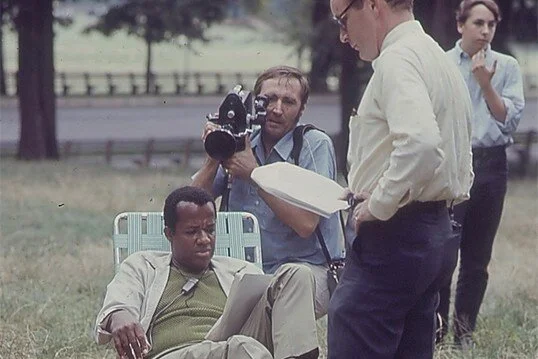

WILLIAM: The sixties were a period of tremendous rebellion on the part of the youth of America, and I was in harmony with that kind of thinking. When one works at a place like the Actor's Studio, one becomes very critical of the work that is being done in front of the camera or on the stage. So I felt that it would be wonderful to apply Cinema Verité techniques to the spontaneity that the Stanislavskysystem encourages in the actor's work.

I was hoping to have any conflict to what I was doing played out in front of the camera by the crew challenging me in what I was doing or criticize me or whatever. But this did not happen until the last scene in the movie, of the crew on the grass, screaming and shouting and shrieking at me because I was doing a lot of what they considered to be bizarre and unorthodox things that were not in lock step with traditional Hollywood feature filmmaking.

You must have been surprised to learn that the crew shot footage of their own, of them talking about you and the way you were working.

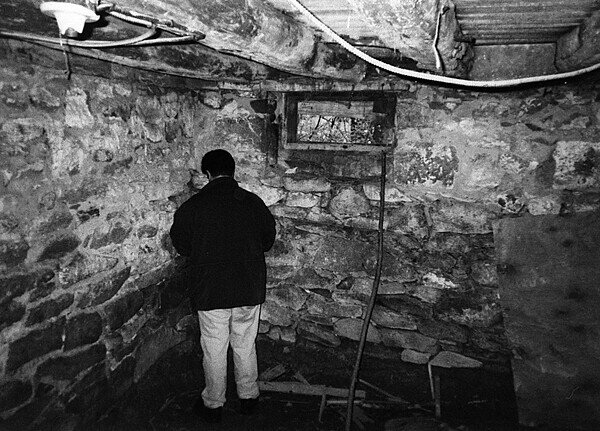

WILLIAM: I didn't think that they were challenging me enough during the course of the shooting, but then they gave me the footage that they shot on their own. I didn't know that they had done this palace revolt, it was something that they surreptitiously stole away and did at the end of a day of shooting after I went home.

They had this closet revolt and it was terribly exciting to me, because I was afraid that the film was not going to work out well, because it didn't have enough conflict.

But when I saw this material I was just elated and I knew that we had a very good film on our hands -- something that would be very fresh and delight audiences, particularly those who were reasonably conversant with the filmmaking process.

Tell me about the title and what it means to you.

WILLIAM: The title is, for me, a very attractive title. I tend to be in love with scientific thinking of one kind or another, and I came across a book called Inquiry Into Inquiries;: Essays In Social Theory, which was written by a very knowledgeable social scientist named Arthur Bentley.

He conceived of the milieu that human beings find themselves as the symbiotaxiplasm. And this symbiotaxiplasm represents those events that transpire in the course of anyone's life that have an impact on the consciousness and the psyche of the average human being, and how that human being also controls or effects changes or has an impact on the environment.

So there's a dialectic or a dialogue that goes on between the action and behavior and thinking of human beings as they move through the events in their lives.

I had the arrogance, the temerity, to introduce the term 'psycho' in the middle of symbiotaxiplasm, making symbiopsychotaxiplasm.

Symbio represents the existence of similarities of one kind or another. Psycho is the mind. Taxi is how the mind reacts and responds to arrangement of reality. And Plasm being the human being. I'm over-simplifying it; you'll have to read the book yourself.

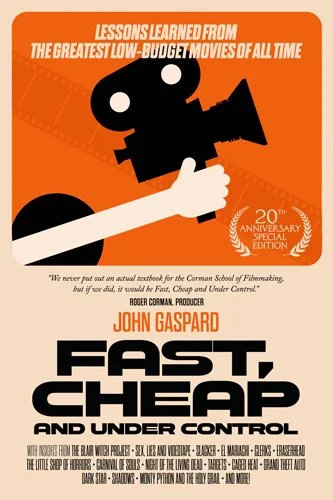

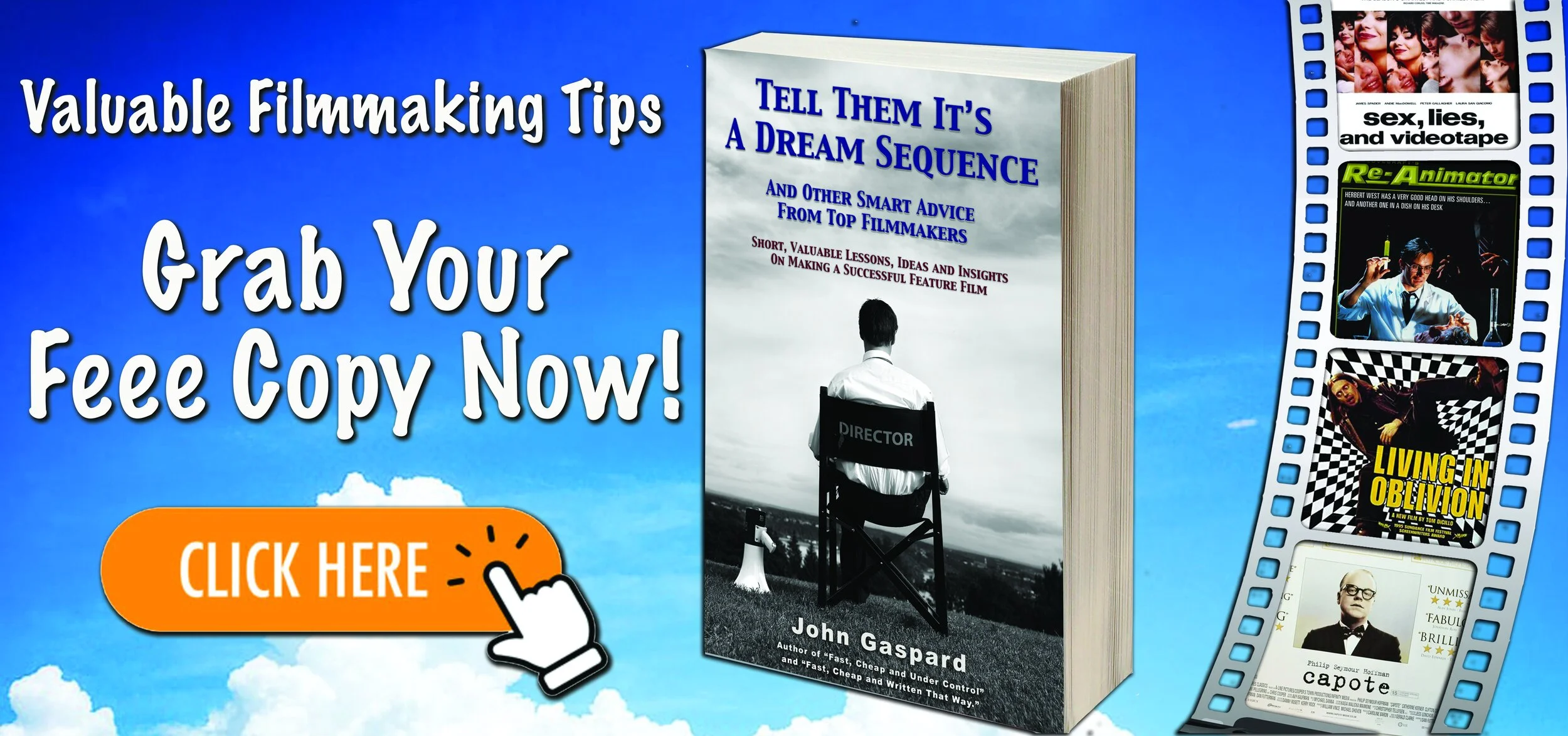

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

When Fast, Cheap & Under Control first hit shelves in 2006, it became the underground handbook for a generation of indie filmmakers. Now, two decades on, this 20th Anniversary Special Edition proves the lessons inside aren't just timeless—they're more essential than ever.

What's changed? Technology. Platforms. Distribution.

What hasn't? The grit, ingenuity, and sheer determination it takes to make a great film with nothing but vision and hustle.

Inside, you'll find:

Exclusive interviews with legends like Steven Soderbergh, Roger Corman, Jon Favreau, Henry Jaglom, Kasi Lemons, Dan O'Bannon, Bob Odenkirk and more

Over 100 images bringing the stories to life

40+ links to trailers, scenes, and supplementary material—turning this book into an interactive master class

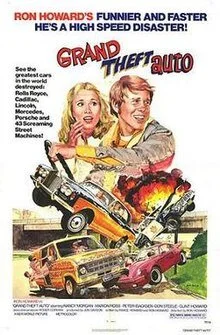

Real-world case studies from 33 groundbreaking low-budget films—from Clerks and El Mariachi to The Blair Witch Project and sex, lies, and videotape

Field-tested lessons from the author's own four features—proof that these principles work in the real world, on set, in the edit room, and on screen

Whether you're shooting on your phone or scraping together a micro-budget, this is your master class in turning limitations into strengths.

No film school required. Just this book.

Roger Corman called it the textbook for his legendary filmmaking school. Now it's your turn to learn from the best.

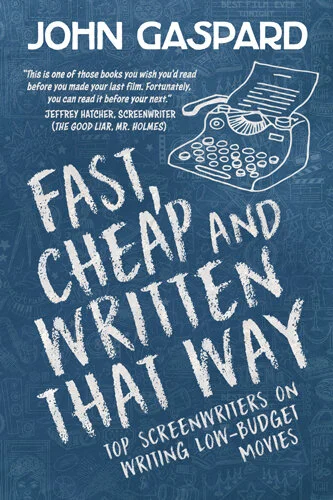

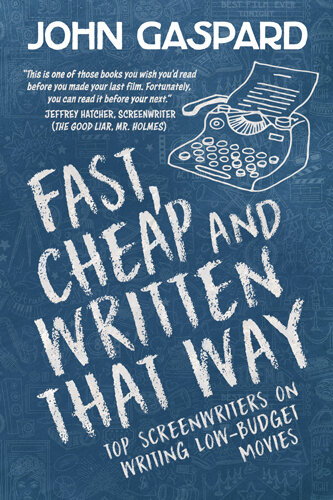

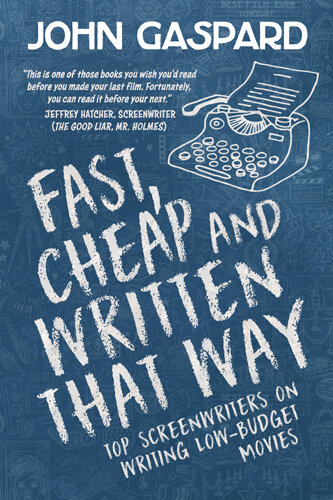

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!