Writer/Director Jonathan Lynn talks about his work on the classic films “Clue” and “My Cousin Vinny,” as well as his comically dark novel, “Samaritans.”

LINKS

A Free Film Book for You: https://dl.bookfunnel.com/cq23xyyt12

Another Free Film Book: https://dl.bookfunnel.com/x3jn3emga6

Fast, Cheap Film Website: https://www.fastcheapfilm.com/

Eli Marks Website: https://www.elimarksmysteries.com/

Albert’s Bridge Books Website: https://www.albertsbridgebooks.com/

YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/BehindthePageTheEliMarksPodcast

“Clue” Trailer: https://youtu.be/KEXdWfsKZ1k

“My Cousin Vinny” Trailer: https://youtu.be/HrfXTjYyenE

“Yes, Minister” Clip: https://youtu.be/KgUemV4brDU

Dying to make a feature? Learn from the pros!

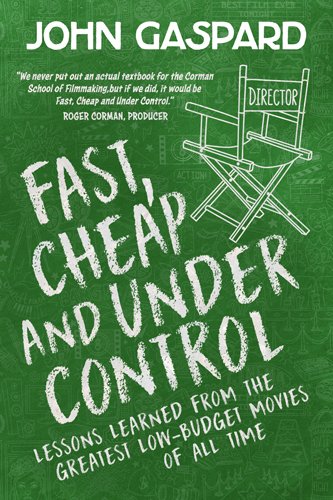

"We never put out an actual textbook for the Corman School of Filmmaking, but if we did, it would be Fast, Cheap and Under Control."

Roger Corman, Producer

★★★★★

It’s like taking a Master Class in moviemaking…all in one book!

Jonathan Demme: The value of cameos

John Sayles: Writing to your resources

Peter Bogdanovich: Long, continuous takes

John Cassavetes: Re-Shoots

Steven Soderbergh: Rehearsals

George Romero: Casting

Kevin Smith: Skipping film school

Jon Favreau: Creating an emotional connection

Richard Linklater: Poverty breeds creativity

David Lynch: Kill your darlings

Ron Howard: Pre-production planning

John Carpenter: Going low-tech

Robert Rodriguez: Sound thinking

And more!

Write Your Screenplay with the Help of Top Screenwriters!

It’s like taking a Master Class in screenwriting … all in one book!

Discover the pitfalls of writing to fit a budget from screenwriters who have successfully navigated these waters already. Learn from their mistakes and improve your script with their expert advice.

"I wish I'd read this book before I made Re-Animator."

Stuart Gordon, Director, Re-Animator, Castle Freak, From Beyond

John Gaspard has directed half a dozen low-budget features, as well as written for TV, movies, novels and the stage.

The book covers (among other topics):

Academy-Award Winner Dan Futterman (“Capote”) on writing real stories

Tom DiCillio (“Living In Oblivion”) on turning a short into a feature

Kasi Lemmons (“Eve’s Bayou”) on writing for a different time period

George Romero (“Martin”) on writing horror on a budget

Rebecca Miller (“Personal Velocity”) on adapting short stories

Stuart Gordon (“Re-Animator”) on adaptations

Academy-Award Nominee Whit Stillman (“Metropolitan”) on cheap ways to make it look expensive

Miranda July (“Me and You and Everyone We Know”) on making your writing spontaneous

Alex Cox (“Repo Man”) on scaling the script to meet a budget

Joan Micklin Silver (“Hester Street”) on writing history on a budget

Bob Clark (“Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things”) on mixing humor and horror

Amy Holden Jones (“Love Letters”) on writing romance on a budget

Henry Jaglom (“Venice/Venice”) on mixing improvisation with scripting

L.M. Kit Carson (“Paris, Texas”) on re-writing while shooting

Academy-Award Winner Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count on Me”) on script editing

Roger Nygard (“Suckers”) on mixing genres

This is the book for anyone who’s serious about writing a screenplay that can get produced!

The Occasional Film Podcast - Episode 102 Transcript

[SOUNDBITE FROM “MY COUSIN VINNY”]

John Gaspard 00:32

That was Joe Pesci and Fred Gwynne in a much-quoted scene from the much-loved film, My Cousin Vinny. Hello, and welcome to episode 102 of The Occasional Film Podcast, the occasional companion podcast to the Fast Cheap Movie Thoughts Blog. I'm that blog’s editor, John Gaspard. In this episode, we're talking to Jonathan Lynn, the director of My Cousin Vinny. But Jonathan Lynn is much more than that. He studied Law at Cambridge, appeared in the Cambridge follies, went with that show to Broadway and the Ed Sullivan Show, and played Motel the Tailor in the original West End production of Fiddler on the Roof.

[SOUNDBITE FROM FIDDLER ON THE ROOF]

He wrote for television and—with Anthony Jay—created Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister, two classic British situation comedies.

[SOUNDBITE FROM YES, MINISTER]

Lynn came to America and wrote and then ended up directing the classic movie comedy Clue. And he did all this by the age of 42. As the satirist Tom Lehrer said,

Tom Lehrer 01:54

It's people like that will make you realize how little you've accomplished. It is a sobering thought, for example, that when Mozart was my age, he had been dead for two years.

John Gaspard 02:39

In my conversation with Mr. Lynn, we talked about what he learned from shooting Clue and went into detail about the making of My Cousin Vinny. But we started our conversation talking about his new novel Samaritans, a caustic look at the American Health System, viewed through the eyes of one hospital, and its staff in Washington DC. What was it about this story that made you think this should be expressed as a novel?

Jonathan Lynn 03:05

I played around with it as a in other forms, because mostly I haven't written—I mean, I've written four or five prose books. I wrote The Complete Yes, Minister and The Complete Yes, Prime Minister, which were enormous bestsellers. But mostly I've written, as you say, in script form, either plays, TV or film scripts. The more I played around with this, the bigger the subject seemed to get. There was no way I could explore the characters of all of these people in a two-hour script, which is actually not very long. A screenplay is 120 pages, that's a pretty well-spaced out. Stage plays, you know, are a similar length we're talking about, you know, usually no more than an hour and a half, especially for comedy. You can make dramas last longer, because you're not asking to be so on the ball and get every joke. But with a comedy you don't want it to go on too long. The famous comedian’s rule, you know, leave them wanting more. And as I kept writing. I found more and more to write about, and it seemed to expand, and it seemed to me that expanding it was good. So, in the end, it seemed to me that its best form would be a novel.

John Gaspard 04:27

As I was reading it, I began to think at first, oh, this is going to be a farce. It's going to be absurd. It's going to be like, Catch 22. It's just going to take an idea and take it to its illogical endpoint. But then as I got into it, I realized, no, this is completely grounded in reality and every bizarre thing that happens seems to have an analogue in the real world and it isn't absurd. I mean, it is absurd. It's kind of like reality. Was that your intention?

Jonathan Lynn 05:03

Well, yes, you're right. It is absurd and it is reality. It's the absurd reality of the healthcare system in the United States, not just in the United States. I mean, I come from Britain where the National Health Service is in a state of collapse, for similar reasons. Because everything is viewed as a business model. And patients are viewed not as patients, but as consumers. And hospitals and healthcare is viewed as something that has to in some way make money. It's worse here, because healthcare in America costs approximately 1/3, more than in any other developed country in the world. In every other developed country, health care is regarded as a right, not a privilege. So, the absurdity here is greater than anywhere else. So, when you mentioned compared to Catch 22, which, by the way, is a very generous compliment that is such a wonderful book. But that's only a little exaggerated too. I mean, that really is what the military was like and World War Two. When you write comedy, you heightened things to exaggerate on the comic effect. But essentially, if they're not true, the reader, or the audience, recognizes that they're not true, and doesn't think it's funny anymore. And so, the balance is always to keep it truthfully observed so that people recognize it and slightly exaggerate it so that people laugh at it.

John Gaspard 06:36

And it is a very funny book. I don't want to talk about it and make it sound like it's dour or serious. I mean, the subject matter is serious, and it is, in many cases, literally life and death. I mean, I just jotted down a couple of quotes that I loved. Referring to healthcare as the ultimate lottery. A student loan, like a diamond, is forever and then I know you put this in for those of us who are fans of your other work to find when Blanche says, I feel you know what I feel flames on the side of my face.

Jonathan Lynn 07:08

Yes, that's a little indulgence for people who are fans of Clue. People really love Clue and that seems to be everybody's favorite moment in the movie.

Madeline Kahn

I hated her soooo much, it, it, flame, flames on the side of my face, breath, breathing, heaving breaths.

Jonathan Lynn 07:08

Because I always saw Blanche. I mean, in God's production, you know, sadly, Madeline Kahn is no longer with us. But if she was, and if we did of production of Samaritans, you know, Madeline Kahn would be the perfect Blanche.

John Gaspard 07:47

She'd be ideal.

Jonathan Lynn 07:49

So, you know, it just sort of came to mind that maybe that's what Blanche say and why not have a little in joke for the benefit of fans of Clue.

John Gaspard 08:02

Absolutely. It's a weird thing to say about a novel, but it's really well researched. At least it appears to be really well researched, which isn't something you think about with a novel. I have written a couple of mystery novels that involve a magician, and it does for me—not being a magician—involve a lot of research to understand that process for me. What was the process for you? Was it research first and then writing or writing leading you down rabbit holes of research?

Jonathan Lynn 08:29

It goes hand in hand to me. The idea comes first. The idea, that the funny idea that hospital beset with raising costs and poor management should decide that they need the head of a Vegas casino as their new CEO, because he understands about check out and check in, beds occupied, and dinners, and has no interest in healthcare. That struck me as a really fun idea as that truthful about the way the health care system is operating here. Then, when I was writing it, I discovered, I read a story in a paper. That said I think it's Aetna, it was one with the big insurance companies, had hired a new CEO, the CEO of Caesars Palace. So, I discovered that life was imitating art in that case. But what happens is that as you can see, when if I got an idea, I started researching simultaneous. So, then I had to find out about hospitals. I knew a bit about hospitals because, well partly I've been a patient more than once, partly my wife taught in two major London teaching hospitals, partly because I have friends who are doctors, and they were very unhappy with the way the situation, the system works here. And you start researching and you start talking to friends and acquaintances or people that you get in touch with and gradually, you discover things that are actually both more appalling and funnier in real life than you would probably ever have thought of as you sat at home trying to make it all up.

I've always found that research led me to greater comic possibilities than I ever thought were there, in anything I've ever written. I think humor is about dark subjects, because it's about serious subjects and I know we're also going to talk about My Cousin Vinny in a few minutes. But you know, that's a perfect example. I mean, that is funny, only because of its terrifying implications that those two kids would have been electrocuted, would have been killed by the state, if they hadn't had a peculiarly argumentative lawyer in Vinny. And you know, so what makes that film both funny and compulsive viewing for people is that it is about something terribly serious. It is finally about life and death. It's a film about capital punishment, although people never talk about it in those terms, but that's at the root of it. So, the answer to your question is yes, I think the more serious the subject, the better the comic possibilities.

John Gaspard 11:16

What special pleasure does novel writing give you that you're not getting as a playwright, or a screenwriter, or a director or an actor?

Jonathan Lynn 11:25

The pleasure is that I only have to please myself. I don't have to worry about, you know, is there some actors who would like this part, or will somebody demand that this character has made more likeable before they'll play it. How can we raise, you know, millions of millions of dollars, in order to get this out before the public. There are all kinds of ways of putting you in a straitjacket when you're creating a play or a film or TV series. That are all to do with the fact that they cost so much money and that, therefore, you need the approval of producers, directors, executives, star actors and everybody else about everything and if you're not very careful, they get compromised out of existence and that often happens. As you know. That doesn't happen if you're writing a book. All I have to do is please myself, and then hopefully find someone who will publish it.

[SOUNDBITE FROM MY COUSIN VINNY TRAILER]

John Gaspard 12:26

The other reason for the call now was, this is the 25th anniversary this year of My Cousin Vinny and I'm sure you've been involved in other interviews and events about that, and those will continue. But I thought it'd be kind of fun to revisit this, you were kind enough to talk to me, I actually don't know how many years ago, but there were some of the questions wanted to ask you about it now that it's 25 years later. But to back up a little bit: So, your first movie, as a director was Clue, which you'd written.

[SOUNDBITE FROM CLUE TRAILER]

And I know you have had before that a lot of experience on stage, both as a director and an actor, but it's a really self-assured directing debut. It's a big movie, although it's in one house, but it's still a big movie with a big cast and a lot going on. What was the biggest lesson you took away from that directing experience?

Jonathan Lynn 13:33

The biggest lesson I took away, although I don't always manage to stick to it, it to trust my own judgments and don't, don't be overly impressed by what I'm told by studio executives. There are things in Clue that I regret, that I should have changed, and I didn't because I was persuaded by the studio that's what I should do, and as a first-time director, I assumed they knew what they were talking about. There are various examples of that. But perhaps the most obvious example is the multiple endings, which was a great mistake to release them in separate movie theaters. Because the whole point about the multiple endings is the ingenuity of the fact that the story could lead to three different outcomes, all of which made sense, and all of which were funny. The film wasn't a success until I put them all together for the video version and they started being seen on TV. I mean, I also learned all kinds of other things that I haven't found about how to use camera, because directing on stage is completely different, especially directing a farce, which Clue is, a broad comedy. Because on stage, you see all the characters and your eye takes in all different sorts of actions. The camera has to focus on little pieces of action one moment at a time. You can't have too many wide shots with eight or nine people in them because they all become too small. You can have some. So, for me it was a big lesson in learning how to photograph comedy as opposed to stage comedy. Staging it was not a problem for me, making sure that I had photographed it exactly right. So, and it was complicated because there were so many people in every scene, that the geography of the scene always had to be clear. You know, the audience needs to know where people are and in the case of Clue, they need to know where people are not, because that of course meant somebody was missing, they could be the murderer. And whenever I've been left alone by the studio, or by the producers to do my thing, my films have been better than when I've been subjected to too much pressure from the parent company.

John Gaspard 13:41

And then we get into My Cousin Vinny. Now, my, some of my questions are going to be based on having re-looked at your book, Comedy Rules. Because there's some stuff in Comedy Rules, although it doesn't refer specifically to Vinny, it feels like it sort of tendentially does. And one of the things you write about there a couple times, and this is I think, first in reference to Yes, Minister, is the idea of the hideous dilemma. Can you just define that for me?

Jonathan Lynn 16:07

Well, yes, I think there has to be. I think all comedy needs a hideous dilemma. And, you know, in, in my book, Comedy Rules, I talked about it in connection with, Yes, Minister, and Yes, Prime Minister, because the politician Jim Hacker, in those series and books, is like all politicians torn between doing the right thing and doing the thing that will either advance his career, or make him look better to the public, or go down better with the press. And these things are nearly always fighting each other. Doing the right thing is often not the safest thing and politicians are always scared of being exposed. Being in government or being in politics is essentially about having two faces, about hypocrisy, and you never want it to be revealed that you said one thing one day and then did something else another day. Now that rule has slightly changed since the advent of Donald Trump, who doesn't seem to care that he's caught out in the lie every day of his life or maybe 10 lies. But it matters to most politicians, and it kills their careers. Sir Humphrey, the senior civil servant, was also always caught in a dilemma. That was some of the nature. Now in My Cousin Vinny, the hideous dilemma is obvious. The two boys are charged with murder that we the audience know they didn't commit, and they have to make a choice. They have to hire Vinny, who has never had conducted a trial. He's only been qualified at the bar for six weeks and he's never done a murder case.

[SOUNDBITE FROM MY COUSIN VINNY TRAILER]

Jonathan Lynn 18:09

They have to hire him. They have nobody else. This is a hideous dilemma for them. The hideous dilemma for Vinny is that he knows that if he fails, his cousin will be executed. I mean, what worse situation could he be in? The hideous dilemma Mona Lisa Vito, Marisa Tomei, is that she's living with this guy who means well, but just can't get it right. All of this is what makes it funny.

John Gaspard 18:38

You know, it could have been played as a completely straight drama right out of John Grisham, because all the elements would be the same.

Jonathan Lynn 18:44

It's a trial movie. It’s just that comedic choices are made instead of dramatic choices. But you're right. That's why it works. Because most trial movies—I mean, I didn't know there was another trial movie that's a comedy from start to finish. There are comedies with trial scenes, but most of them are rather treated rather frivolously. In Vinny, I treated the situation with the utmost seriousness. And I think that's why it's funny, because it's so frightening.

John Gaspard 19:16

Exactly. Another thing you mentioned in the book Comedy Rules that I think applies really nicely here is the concept that it helps to be an outsider, which Vinny clearly is. And that gives you a great way into the story. Did your experience sort of as an outsider, a British director working in America, was that also helpful?

Jonathan Lynn 19:39

When I look at the history of Hollywood movies, one has to assume that that is helpful. If you look at the extraordinary number of really good directors who came from Europe mainly but also from other cultures to Hollywood and one of the best things about Hollywood that has to be said, that’s good about Hollywood, that it is not at all xenophobia. It welcomes anyone from anywhere. But if you look, I mean, Billy Wilder is my favorite comedy director. He was Viennese, Fred Zimmerman was from Vienna, Milos Forman is from Czechoslovakia. Michael Curtiz is from Hungary, and you could go on all day. I mean, a colossal number of the greatest Hollywood directors of—Alfred Hitchcock from Britain—are from somewhere else. And I think it helps. I think as an outsider, you see it maybe more clearly. People always talk to me about the fact that the South is presented differently in My Cousin Vinny than in most American films. That's because I think most American films are directed by northerners and they see the South as some strange, foreign place. To me, the South and the North they're all just America. I mean, the differences, there are obvious differences, but they're still part of American culture, all of which is, or was that time, foreign to me.

John Gaspard 21:01

I don't know, I'm one of those people who I'm sure you're running this all the time, who say if you're flipping channels, and My Cousin Vinny is on, that's it. You're gonna watch the rest of the movie.

Jonathan Lynn 21:10

That's really nice. I feel like that about some movies. I feel like The Godfather Part One and Two and you know, some other movies. I mean, if I see the Godfather on TV, if I happen to stumble across it, I have to keep watching. And, you know, there are some other movies. It's very nice to that people feel like that about Vinny.

John Gaspard 21:32

Yeah, everything came together in that movie, the script is very strong the way you directed it. And I don't mean just where you put the camera, or how you cast it. All those are great and you have a really very clean, non-intrusive visual style, which allows comedy to play really, really well. But between the script and the directing, and the way it's edited, all the pieces are there as a mystery, which it is sort of. It is completely fair. All the clues are given, and they're given so subtly, the how long does it take to cook grits, which is an important thing, is almost a throwaway line. You don't even think about it, it's perfectly in character for that conversation to happen. Just even the shot of the boys pulling away from the store at the beginning, where the curb can be seen on the left side of the screen, and you don't make a point of the fact that they don't go over the curb, because we don't know that's a fact. But when we see the photos later, we—if we had any doubts at all—knowthat wasn't their car, because they didn't go over that curb. I mean, it's that sort of attention to detail, you wouldn't necessarily see in a quote unquote, light comedy. But I think it’s what makes it a perennial favorite.

Jonathan Lynn 22:44

Perhaps it's because I have a degree in law and I wanted it to be legally good. And perhaps because I've seen a number of trial movies that I really, really liked, like The Verdict and Absence of Malice and of course, To Kill a Mockingbird, there's a lot of great, Anatomy of a Murder. One of those are films that I think are full of tension and suspense and hold the audience's attention and I think I felt that was important. You can't make the whole movie about a trial unless the trial is dramatically effective from start to finish. So, yes, I approached it as a drama, except that we made comedic choices all the way through.

John Gaspard 23:24

What was your rehearsal process like? Did you have time for rehearsal?

Jonathan Lynn 23:27

No, there was no rehearsal. I discussed it with Joe Pesci and Joe said he hated rehearsal. He felt it took away his spontaneity and of course, he liked to rehearse a scene on the morning that we were shooting it, but he didn't want any advance rehearsal. Now, one of the jobs of the director, maybe the main job of the director is just to get the best work out of all the people in the movie. If you're leading actor doesn't want to rehearse, there's no point in trying to make them rehearse. It won’t improve the result. So, we didn't have any rehearsal and all the rehearsals were just on the day of each scene.

John Gaspard 24:06

Well, that sort of jumps us right to my next question, which is going back to Comedy Rules again. This is rule number 140, which was remember the old English proverb you don't buy a dog and bark yourself. Talk to me about how that applies to your work as a director, because you are also an actor, and you're also a writer.

Jonathan Lynn 24:28

I never demonstrate how everything should be done. I never say play it like this. I never say, say it this way. I assume that the actors that I've got are high level, skilled professionals. And what I want them to do is bring what they can bring to something that I already have in mind and that the writer—which may or may not have been me—has already written. You know, with really good actors, with leading actors you know, you don't tell the movie star, this is how you play the scene and then demonstrate, because they would, you know, rightly send for their limo and go home. That's not what they're there for. They're there to bring what they can bring to the proceedings. And what you have to do as a director is have what know what you have in mind and meld it with what your actors bring. And that's why casting is so absolutely critical, because if you miscast a part, you know, it will never work, or will certainly never work the way you intended it to.

John Gaspard 25:37

You mentioned Billy Wilder, and I'm going to mention another rule from Comedy Rules, because there's a lot of good ones in there. Rule 149 is the last part of every film and play is a race to the finish between the show and the audience. Which I think is something Wilder would have agreed with. And you went on to add, the show must get there first. One of the things that makes, I think, Vinny so successful is that when the end is there, it's there. We zip right to the end. You don't hang around, there's not a lot of extraneous stuff. It's like the movie is over and we're out. How hard was that to achieve?

Jonathan Lynn 26:17

Well, it was interesting, because of course, that was done in the production rewrite. Dale wrote a wonderful script, but there were things that still needed sorting out and Fox hired me to do the production rewrite. And in the original draft that I was given, we never knew who committed the murders. You never knew what the real story was. So, that was a problem. For me, that was a problem. You can't have a trial movie without knowing what actually happened. Now, obviously, we didn't want to see what actually happened, because that would have been time consuming and boring. That's the problem with a Who Done It. That's why Hitchcock never made a Who Done It, because in a Who Done It, there's always a scene at the end, when the detective explains what really happens and that's always really dull. I made fun of that in Clue, with the butler’s ludicrous explanation of everything. But I made it into a joke, because that film was a parody of a murder mystery. But in this case, we didn't need to see it all on camera. But we did need to know that the real murderers had been found and had been caught and that it all made sense. The other thing is that we didn't want to have the jury. Once it was clear that the two boys have not committed the murder, we have to get out of that trial as fast as possible. So, that meant it didn't have to it couldn't go to the jury. We couldn't have a boring scene when they came back and the judge said, you know, have you reached a verdict? Yes, Your Honor and reading out the verdicts and all that stuff that you see on television every week. So, it meant that we had to have the prosecutor do the right thing, which was very good anyway, because for me, there's no bad guy. The one most interesting thing about film, I think, is there is no villain. The court system, the justice system is the antagonist. So, we have to get out of that fast. So, it meant that the prosecutor did the right thing and simply withdrew the case. He just said, you know, we're not proceeding with this. So, that was the end of the trial. And that meant we could get out of that trial, in terms of screen time, probably five minutes sooner then if we'd gone through the whole thing of it going to the jury.

John Gaspard 28:27

Now, is there anything looking back in the movie that you wish you would have done differently?

Jonathan Lynn 28:30

Well actually, no. When I see the movie now, which I don't very often, but I you know, I have seen it occasionally. I'm really pleased with it. I have to say, most of my films, I see plenty of things I would like to change and that one, I think, you know, was a lot of luck. We made all the right choices, I think. I don't see anything I would want to change.

John Gaspard 28:53

I would agree. Is there anything any consistent thing you hear from fans about that movie that if someone mentions it, you know, they're gonna say this or that?

Jonathan Lynn 29:04

No, I get a lot of terrific response from judges and attorneys, who will say that it's legally the most accurate film that's ever been produced by Hollywood. I've met a number of federal judges who use it in their teaching at law schools, especially in the teaching of evidence. That's very gratifying. I was asked to speak at a couple of legal conventions to federal judges and others, not about the law, of course, which they know more about than I do, about how Hollywood treats trials and legal firms. So, they're very gratifying group of people. And then of course, they're just favorite moments that people refer to, which always happens in films, just like we were talking about in Clue, like Mrs. White’s lines about the flames on the side of my face. It seems that a large number of people quote Vinny’s line ‘Two Youts,” and there are a number of other moments in the film which people refer to with the great affection.

[SOUNDBITE: MORE FROM THE MY COUSIN VINNY TRAILER]

John Gaspard 30:23

Thanks to Jonathan Lynn for taking the time to talk to me about his new book Samaritans, as well as Clue and My Cousin Vinny. If you liked this interview, you can find lots more just like it, including the transcript of an earlier interview with Mr. Lynn, covering other facets of My Cousin Vinny on the Fast Cheap Movie Thoughts blog. Plus, more interviews can be found in my books: Fast, Cheap And Under Control: Lessons Learned From The Greatest Low Budget Movies Of All Time, and its companion book of interviews with screenwriters, called Fast, Cheap And Written That Way. Both books can be found on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Google Play and Apple books. And while you're there, check out my mystery series of novels about magician Eli Marks and the scrapes he gets into. The entire series, starting with The Ambitious Card, can be found on all those online retailers I just mentioned in paperback hardcover eBook and audiobook formats. You can find information on those books and all the other books at Albertsbridgebooks.com. That's Albertsbridgebooks.com. And that's it for episode 102 of The Occasional Film Podcast, produced at Grass Lake studios. Original Music by Andy Morantz. Thanks for tuning in, and we'll see you next time.